Ancient African Literacy Science and Education

The words literacy, science and education arent really synonymous with the African continent are they? What’s crazy is that that mindset is totally opposite of the truth. There are many literary and scientific achievement that predate many of those classically attributed to other parts of the world. Here are some examples below and this is just scratching the surface.

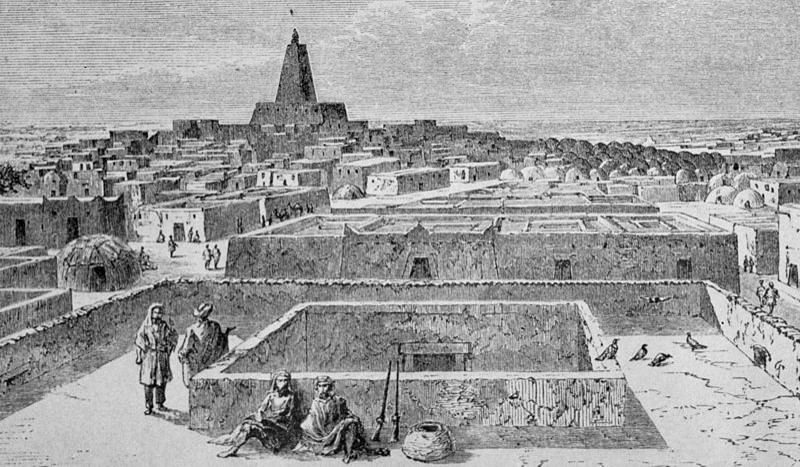

Timbuktu, Mali

- West African Scholars of the 16th Century Were Known to Have Thousands of Books

- a library of a little over 1,000 books was considered child’s play.

- West African scholar Professor Ahmed Baba of Timbuktu is recorded as saying he had the smallest library of all his friends and colleagues with “only 1600 volumes.”

- West African scholar Professor Ahmed Baba of Timbuktu is recorded as saying he had the smallest library of all his friends and colleagues with “only 1600 volumes.”

- Many old West African families have private library collections that go back hundreds of years.

- The Mauritanian cities of Chinguetti and Oudane have a total of 3,450 hand written mediaeval books.

- There may be another 6,000 books still surviving in the other city of Walata.

- Some date back to the 8th century AD. There are 11,000re 11,000

English: World English Bible - WEB

301 Moved Permanently Moved Permanently The document has moved .

WP-Bible plugin books in private collections in Niger.

- Finally, in Timbuktu, Mali, there are about 700,000 surviving books.

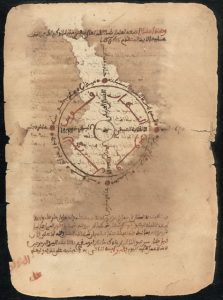

- Concerning these old manuscripts, Michael Palin, in his TV series Sahara, said the imam of Timbuktu

- “has a collection of scientific texts that clearly show the planets circling the sun.

- They date back hundreds of years … Its convincing evidence that the scholars of Timbuktu knew a lot more than their counterparts in Europe.

- Timbuktu in Mali is home to one of the world’s oldest universities, Sankore, which had libraries full of manuscripts mainly written in Ajami (African languages, such as Hausa in this case, written in a script similar to “Arabic”) in the 1200s AD.

- When Europeans and Western Asians began visiting and colonizing Mali from 1300s-1800s AD, Malians began to hide the manuscripts in basements, attics and underground, fearing destruction or theft by foreigners.

- In the fifteenth century in Timbuktu the mathematicians knew about the rotation of the planets, knew about the details of the eclipse,

- they knew things which we had to wait for 150 almost 200 years to know in Europe when Galileo and Copernicus came up with these same calculations and were given a very hard time for it.”

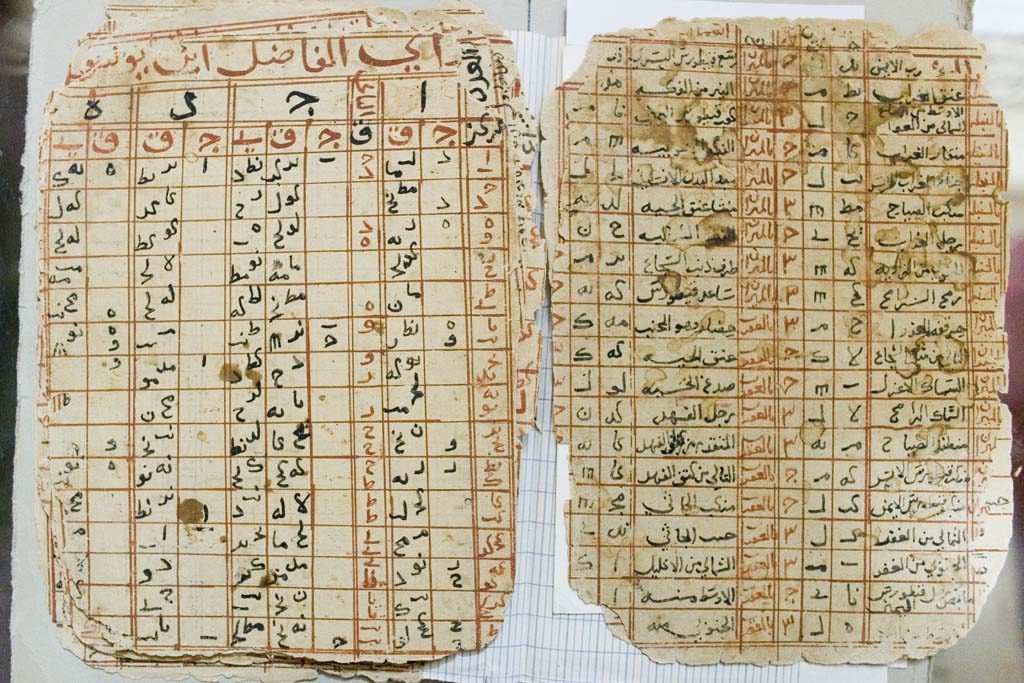

Astronomy tables

- The Malian city of Timbuktu had a 14th century population of 115,000 – 5 times larger than mediaeval London.

- Mansa Musa, built the Djinguerebere Mosque in the fourteenth century.

- According to Professor Henry Louis Gates, 25,000 university students studied at the University Mosque and the Oratory of Sidi Yayia.

- There were over 150 Koran schools in which 20,000 children were instructed.

- London, on the other hand by that time, had a total 14th century population of 20,000 people….let that sink too.

- National Geographic recently described Timbuktu as the Paris of the mediaeval world, on account of its intellectual culture.

The majority of manuscripts were written in Arabic, but many were also in local languages, including Manding, Songhay and Tamasheq. The dates of the manuscripts ranged between the late 13th and the early 20th centuries (i.e., from the Islamisation of the Mali Empire until the decline of traditional education in French Sudan). Their subject matter ranged from scholarly works to short letters. The manuscripts were passed down in Timbuktu families and were mostly in poor condition.[4] Most of the manuscripts remain unstudied and uncatalogued, and their total number is unknown, affording only rough estimates. A selection of about 160 manuscripts from the Mamma Haidara Library in Timbuktu and the Ahmed Baba collection were digitized by the Tombouctou Manuscripts Project in the 2000s.

The Timbuktu Manuscripts Project was a project of the University of Oslo running from 1999 – 2007, the goal of which was to assist in physically preserving the manuscripts, digitize them and building an electronic catalogue, and making them accessible for research.

It was funded by the government of Luxembourg along with the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), the Ford Foundation, the Norwegian Council for Higher Education’s Programme for Development Research and Education (NUFU), and the United States Ambassador’s Fund for Cultural Preservation.

Among the results of the project are: reviving the ancient art of book binding and training a solid number of local specialists; devising and setting up an electronic database to catalogue the manuscripts held at the Institut des Hautes Études et de Recherche Islamique – Ahmad Baba (IHERIAB); digitizing a large number of manuscripts held at the IHERIAB; facilitating scholarly and technical exchange with manuscript experts in Morocco and other countries; reviving HERIAB’s journal Sankoré; and publishing the splendidly illustrated book, The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Historic City of Islamic Africa.

The Tombouctou Manuscripts Project is a separate project run by the University of Cape Town. In a partnership with the government of South Africa, which contributed to the Timbuktu trust fund, this project is the first official cultural project of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development. It was founded in 2003 and is ongoing. They released a report on the project in 2008.

As well as preserving the manuscripts, the Cape Town project also aims to make access to public and private libraries around Timbuktu more widely available. The project’s online database is accessible to researchers only. In 2015 it was announced that the Timbuktu trust fund would close after receiving no more funds from the South African government.

Astronomy – Namoratunga in Kenya

- Ruins of a 300 BC astronomical observatory was found at Namoratunga in Kenya.

- Africans were mapping the movements of stars such as Triangulum, Aldebaran, Bellatrix, Central Orion, etcetera, as well as the moon, in order to create a lunar calendar of 354 days.

It is easily visible on the Lodwar – Kalokol roadside, 20 meters from the road. Namoratunga II (3°25′22″N 35°48′10″E) contains 19 basalt pillars, aligned with 7 star systems: Triangulum, Pleiades, Bellatrix, Aldebaran, Central Orion, Saiph, and Sirius. Namoratunga means “people of stone” in the Turkana language. Mark Lynch and L.H. Robbins discovered the site in 1978. Lynch believes the basalt pillars tie the constellations or stars to the 12-month 354-day lunar calendar of Cushitic speakers of southern Ethiopia. The pillars align with the movements of the 7 constellations corresponding to a 354-day calendar. The pillars are surrounded by a circular formation of stones. One grave with a pillar on top exists in the area. Namoratunga I (2°23′0.04″N 36°8′2.52″E) contains a similar grave but no pillars.

Ethiopian Script

The Ethiopian script of the 4th century AD influenced the writing script of Armenia.

The Ethiopian script of the 4th century AD influenced the writing script of Armenia.- A Russian historian noted that: “Soon after its creation, the Ethiopic vocalised script began to influence the scripts of Armenia and Georgia.

- D. A. Olderogge suggested that Mesrop Mashtotz used the vocalised Ethiopic script when he invented the Armenian alphabet.”

Congolese Abacus

- Africans pioneered basic arithmetic. The Ishango bone is a tool handle with notches carved into it found in the Ishango region of Zaïre (now called Congo) near Lake Edward. The Ishango bone was found in 1960 by Belgian Jean de Heinzelin de Braucourt while exploring what was then the Belgian Congo. It was discovered in the area of Ishango near the Semliki River.It is a dark brown length of bone, the fibula of a baboon, with a sharp piece of quartz affixed to one end, perhaps for engraving.

- On the tool are 3 rows of notches.

- Row 1 shows three notches carved next to six, four carved next to eight, ten carved next to two fives and finally a seven.

- Row 2 shows eleven notches carved next to twenty-one notches, and nineteen notches carved next to nine notches. This represents 10 + 1, 20 + 1, 20 – 1 and 10 – 1

- Finally, Row 3 shows eleven notches, thirteen notches, seventeen notches and nineteen notches. 11, 13, 17hes. 11, 13, 17

English: World English Bible - WEB

301 Moved Permanently Moved Permanently The document has moved .

WP-Bible plugin and 19 are the prime numbers between 10 and 20.

- = it’s a calculator

The artifact was first estimated to have originated between 9,000 BC and 6,500 BC. However, the dating of the site where it was discovered was re-evaluated, and it is now believed to be more than 20,000 years old. The Ishango bone is on permanent exhibition at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels, Belgium.

Some mathematicians, scientists and archaeolgists believe the three columns of asymmetrically grouped notches imply that the implement was used to construct a numeral system.

The central column begins with three notches and then doubles to 6 notches. The process is repeated for the number 4, which doubles to 8 notches, and then reversed for the number 10, which is halved to 5 notches. These numbers may not be purely random and instead suggest some understanding of the principle of multiplication and division by two. The bone may therefore have been used as a counting tool for simple mathematical procedures.

In the book How Mathematics Happened: The First 50,000st 50,000

English: World English Bible - WEB

301 Moved Permanently

Moved Permanently

The document has moved .

WP-Bible plugin Years, Peter Rudman argues that the development of the concept of prime numbers could have come about only after the concept of division, which he dates to after 10,000 BC, with prime numbers probably not being understood until about 500 BC. He also writes that “no attempt has been made to explain why a tally of something should exhibit multiples of two, prime numbers between 10 and 20, and some numbers that are almost multiples of 10.

Ethiopia – Counting Board

Although the oldest known evidence of the ancient counting board game

Although the oldest known evidence of the ancient counting board game- Gebet’a or “Mancala” as its more popularly known, comes from Yeha (700 BC) in Ethiopia

- The game forces players to strategically capture a greater number of stones than one’s opponent.

- The game usually consists of a wooden board with 2 rows of 6 holes each, and 2 larger holes at either end.

- However, in antiquity, the holes were more likely to be carved into stone, clay or mud like the example from Medieval Aksum, shown at right.

- More advanced versions found in Central and East Africa, such as the Omweso, Igisoro and Bao, usually involve 4 rows of 8 holes each.

Egyptian Algebra, Trigonometry and Mathematics

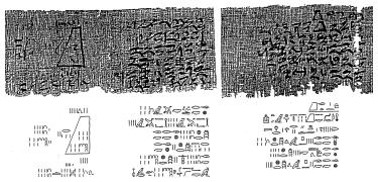

“Moscow” Papyrus (2000 BC)

“Moscow” Papyrus (2000 BC) - Housed in Moscow’s Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, the so-called “Moscow” papyrus, was purchased by Vladimir Golenishchev sometime in the 1890s.

- Written in hieratic from perhaps the 13th dynasty in Kemet, the papyrus is one of the world’s oldest examples of use of geometry and algebra.

- The document contains approximately 25 mathematical problems, examples include

- the length of a ship’s rudder

- the surface area of a basket

- the volume of a frustum (a truncated pyramid)

- ways of solving for unknowns

Purchased by Alexander Rhind in 1858 AD, the so-called “Rhind” Papyrus

Purchased by Alexander Rhind in 1858 AD, the so-called “Rhind” Papyrus- Written by the scribe, Ahmose:

- “Accurate reckoning for inquiring into things, and the knowledge of all things, mysteries…all secrets… This book was copied in regnal year 33, month 4 of Akhet, under the majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Awserre, given life, from an ancient copy made in the time of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt Nimaatre. The scribe Ahmose writes this copy…”

- The first page contains 20 arithmetic problems, including addition and multiplication of fractions, and 20 algebraic problems, including linear equations.

- The second page shows how to calculate the volume of rectangular and cylindrical granaries, with pi (Π) estimated at 3.1605.

- There are also calculations for the area of triangles (slopes of a pyramid) and an octagon.

Mali – Dogon Astronomers

** disclaimer – this discovery is so amazing it seems like scifi – but just keep in mind truth is stranger than fiction

The Dogon people are an indigenous tribe who occupy a region in Mali, south of the Sahara Desert in Africa. There are about 100,000 members in the tribe.

They are a reclusive tribe of cave and hillside-dwelling farming people inhabiting a sparse, rocky plateau in southeastern Mali, West Africa. They live in the Homburi Mountains near Timbuktu.

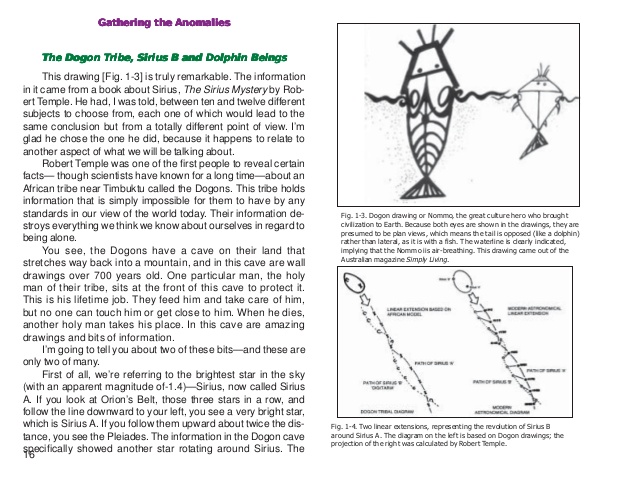

The first Western scientists to visit and study the Dogon people were French anthropologists Drs Marcel Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen, who initially made contact with them in 1931, and continued to research them for the next three decades, culminating in a detailed study conducted between 1946-1950. During their work, these anthropologists documented the traditional mythology and sacred beliefs of the Dogon, which included an extraordinary body of ancient lore regarding Sirius the brilliant, far-distant Dog Star.

Their priests told them of a secret Dogon myth about the star Sirius (8.6 light years from the Earth. The priests said that Sirius had a companion star that was invisible to the human eye. They also stated that the star moved in a 50-year elliptical orbit around Sirius, that it was small and incredibly heavy, and that it rotated on its axis.

Their priests told them of a secret Dogon myth about the star Sirius (8.6 light years from the Earth. The priests said that Sirius had a companion star that was invisible to the human eye. They also stated that the star moved in a 50-year elliptical orbit around Sirius, that it was small and incredibly heavy, and that it rotated on its axis.

Sirius – which we now call Sirius A – was not seen through a telescope until 1862 and was not photographed until 1970.

The Dogon name for Sirius B (Po Tolo) consists of the word for star (tolo) and “po,” the name of the smallest seed known to them. By this name they describe the star’s smallness — it is, they say, “the smallest thing there is.” They also claim that it is “the heaviest star,” and white.

The tribe claims that Po is composed of a mysterious, super-dense metal called sagala which, they declare, is heavier than all the iron on Earth. Not until 1926 did Western science discover that this tiny star is a white dwarf a category of star characterized by very great density. In the case of Sirius B, astronomers have estimated that a single cubic metre of its matter weighs about 20,000 tons.

Many artifacts were found describing the star system, including a statue examined by Dieterlen that is at least 400 years old.

They go on to say that it has an is elliptical orbit, with Sirius A at one foci of the ellipse (as it is), that the orbital period is 50 years (the actual figure is 50.04 +/- 0.09 years), and that the star rotates on its own axis (it does).

The Dogon also describe a third star in the Sirius system, called “Emme Ya” (“Sorghum Female”). In orbit around this star, they say, is a single satellite. To date, Emme Ya has not been identified by astronomers.

In addition to their knowledge of Sirius B, the Dogon mythology includes Saturn’s rings, and Jupiter’s four major moons. They have four calendars, for the Sun, Moon, Sirius, and Venus, and have long known that planets orbit the sun.

You know what’s really sad – Carl Sagan – scifi guy…said that there’s no way indigenous African people’s could have come up with such knowledge. He claimed a European must have wandered through the region with this knowledge. UFO conspiracy theorists claim that aliens brought them this technology…check out my cool videos section on UFOlogy and the fallacies about visiting aliens or even ancientaliensdebunked.com as well that debunks ancient alien builder theories.